In the year 2060, the city of Arnhem declared itself the first ecosystem-neutral city of the Netherlands. Arnhem became iconic because it set nature and ecological considerations alongside human society as equally important priorities in spatial planning activities. The experimental incorporation of nature to the extent of declaring ecosystem-neutrality marks the beginning of a new relationship of humanity and nature.

In the year 2060, the city of Arnhem declared itself the first ecosystem-neutral city of the Netherlands. Arnhem became iconic because it set nature and ecological considerations alongside human society as equally important priorities in spatial planning activities. The experimental incorporation of nature to the extent of declaring ecosystem-neutrality marks the beginning of a new relationship of humanity and nature.

In the year 2060, the city of Arnhem declared itself the first ecosystem-neutral city of the Netherlands. Arnhem became iconic because it set nature and ecological considerations alongside human society as equally important priorities in spatial planning activities. The experimental incorporation of nature to the extent of declaring ecosystem-neutrality marks the beginning of a new relationship of humanity and nature.

The great flood of 2040

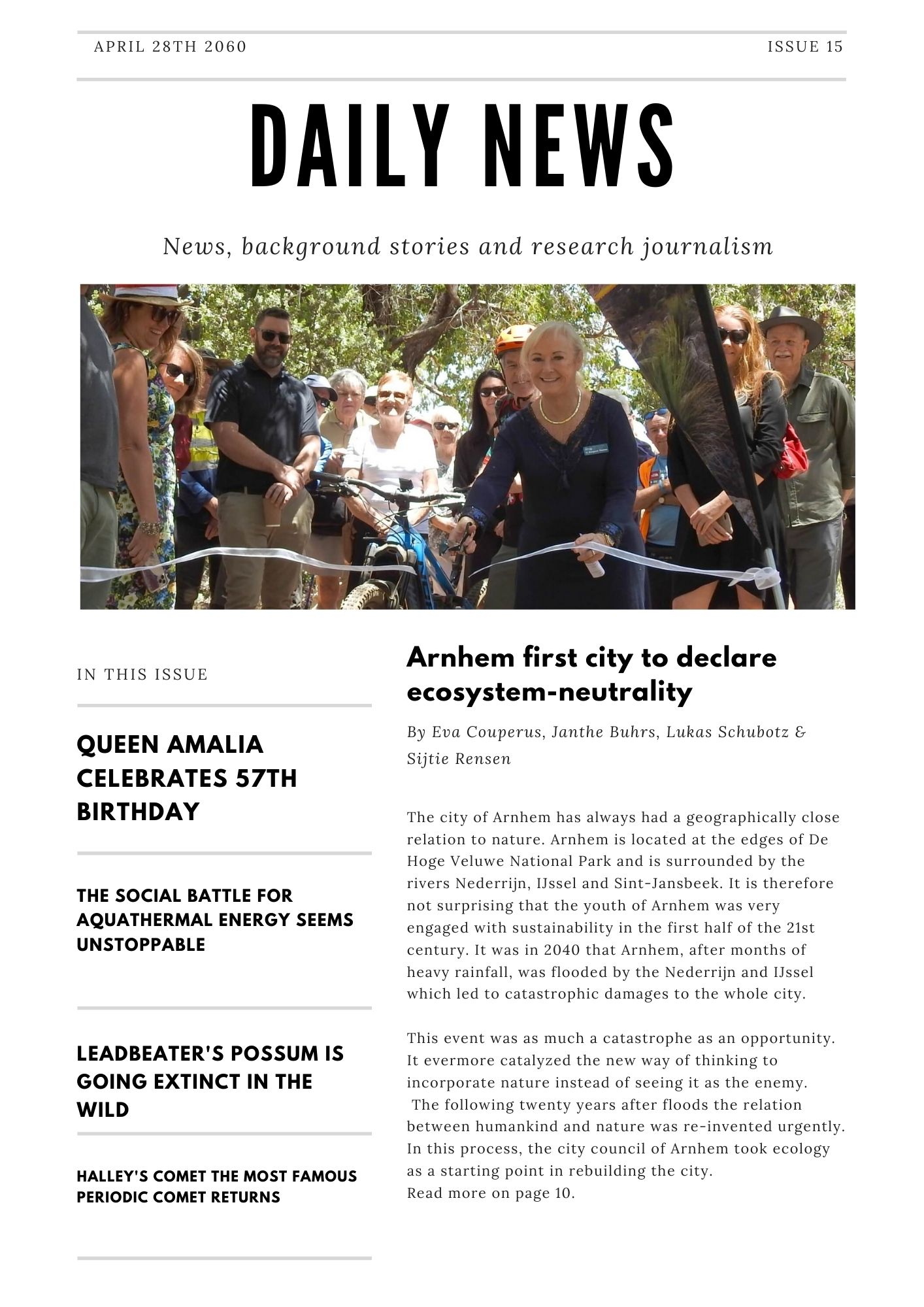

The city of Arnhem has always had a close relation to nature, due to its geography. Arnhem is located at the edges of De Hoge Veluwe National Park and is surrounded by the rivers Nederrijn, IJssel and Sint-Jansbeek. It is therefore not surprising that the youth of Arnhem was very engaged with sustainability in the first half of the 21st century. Still, in the process of achieving the CO2 targets of 2050, it was recognized that climate change and sustainability could not be solved solemnly by becoming CO2 neutral, but only by making substantial changes to living and housing within and alongside the natural sphere. It was in 2040 that Arnhem, after months of heavy rainfall, was flooded by the Nederrijn and IJssel which led to catastrophic damages to the whole city. The city centre was affected worst. Roads and houses flooded, leaving 10,000 households with nothing but water up to their knees. The time after the evacuation was a daunting period in which people were brutally confronted with the fact that engineered dikes could no longer protect them from the consequences of climate change. The flood was a catastrophe, but it turned out to be an opportunity as well. It catalysed even more the new way of thinking, in which nature was incorporated rather than seen as the enemy. The twenty years after floods the relation between humankind and nature was re-invented. In this process, the city council of Arnhem took ecology as a starting point in rebuilding the city.

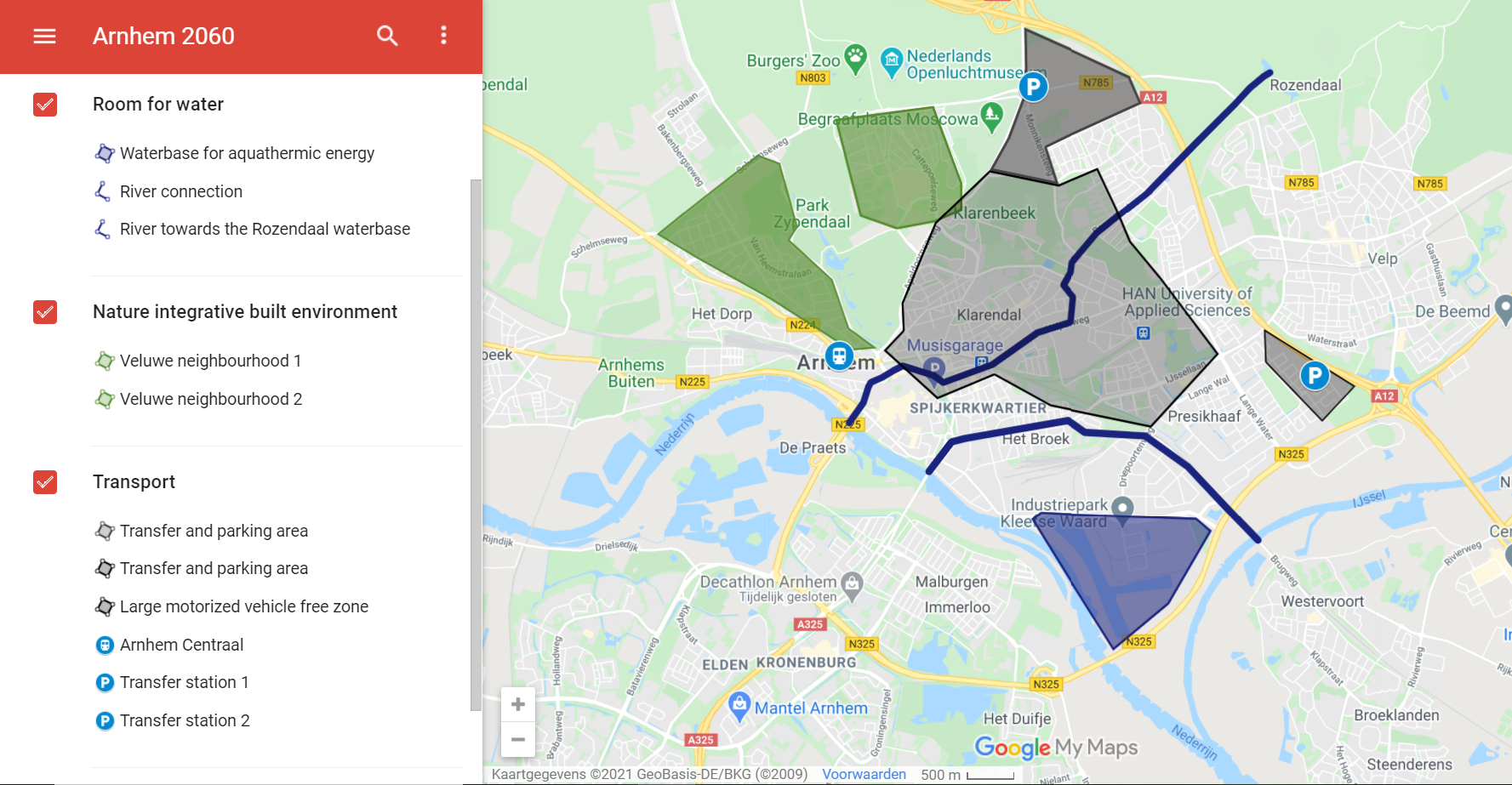

Map of Arnhem in 2060

Leaving the ark: The rebuild after the flood

The first steps taken by the municipality was to integrate the river through the city. Main roads in the city centre of Arnhem were broken up and turned into canals. This way the impact and power of the Nederijn and IJssel on the dikes surrounding the city was reduced. Other asphalt roads were transformed into, for instance, vegetated cobblestones, allowing more greenery to return to the city and the soil to absorb rainfall more quickly and homogeneously. As a result of the changed urban environment, transport in the city centre was mainly carried out by (cargo) bikes, small electric vehicles and boats. People who still owned a car could park them at large transportation stations just outside of the centre. Furthermore, the flooded industry site of the Kleefse Waard was transformed into a waterbase to generate aqua-thermal energy for Arnhem, protecting jobs and providing more over the years.

The emergence of eco-pauperism

The infrastructure of Arnhem was rebuilt rather quickly, but the rebuilding of citizens’ private property was not such smooth sailing. From 2040 onwards, Arnhem lived through a period of renewal and natural regeneration. New policies were created, and subsidies granted by the state to rebuild Arnhem with environmentally friendly materials only. New housing developments in the north, closest to the Veluwe, were fully integrated with nature using vertical gardening and materials that supported the ecosystem of the National Park. These climate-adaptive neighbourhoods inspired the residents of Arnhem to create their own climate-adaptive parks and gardens near their homes. Especially the northern parts of Arnhem, with many high-income households. made big steps, creating a large number of parks and roof gardens. However, in the south of Arnhem, populated with mainly lower- and middle-income households, it proved to be more difficult to put plans into practice. Despite financial support from the municipality for renovations required after the flood, this was mostly carried out at the expense of homeowners and landlords, causing rents to rise. This resulted in the rise of eco-pauperism, a term that is retrospectively coined by (van Dijk, 2096). Eco-pauperism denotes the result of large-scale policy-induced social and economic processes, set into motion to benefit the environment but disadvantaging a large proportion of households.

Vertical gardens

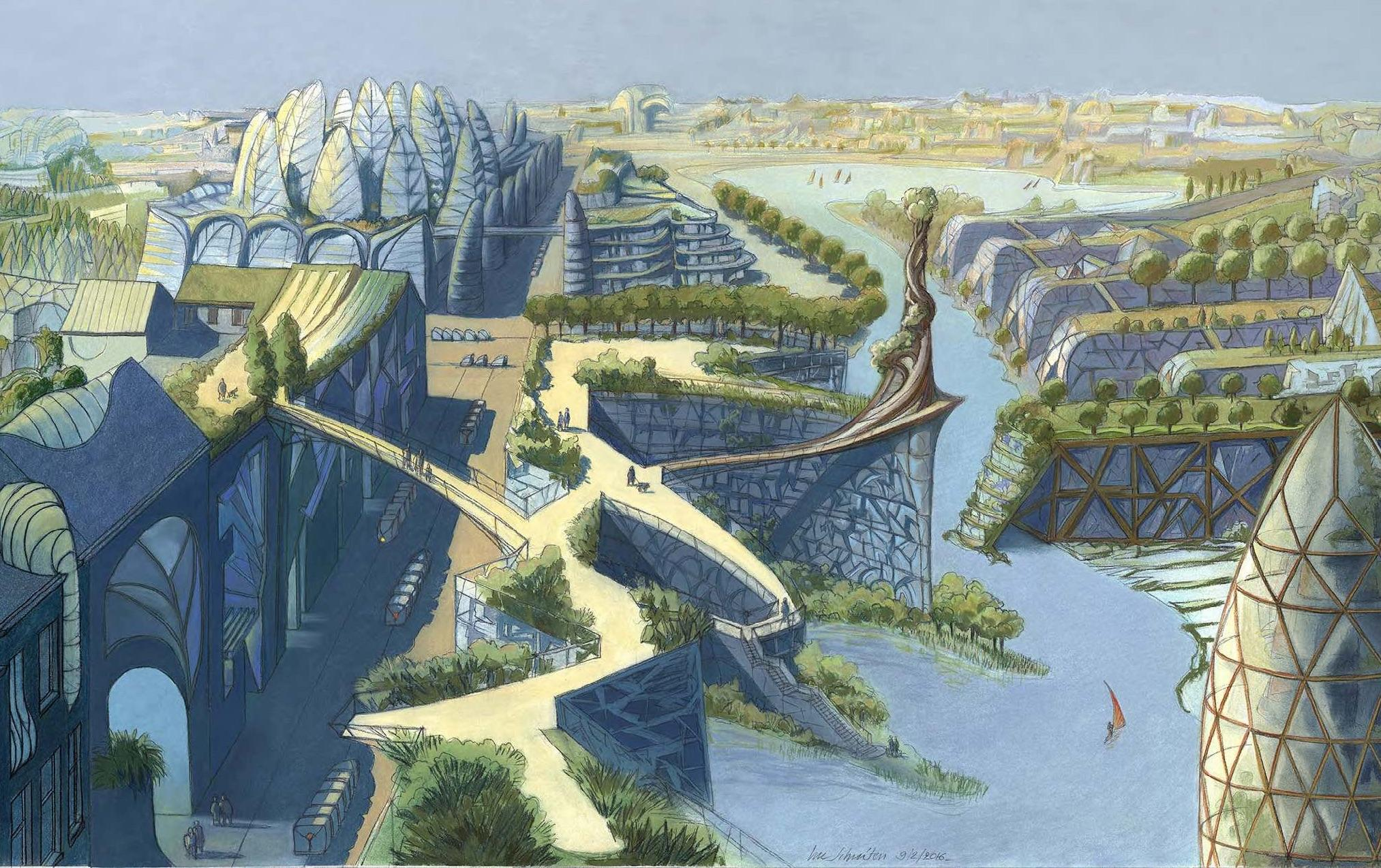

Public space in Arnhem nature city 2060

A new zeitgeist and the declaration of ecosystem neutrality

Life in Arnhem changed drastically on both the outside and inside. Despite great complications, diary analyses show that over time, the citizens’ minds were more and more occupied with sustainability. The overall prevailing theme was the search for ways of connecting to nature, regardless of socioeconomic status. The zeitgeist of the prior 20 years had, catalysed through the flood and subsequent urban interventions, escaped the confines of its youth-based niche and affected greater parts of the population. It called for a new perspective, a recognition and acknowledgement of the natural world as fully equal to human society.

Arnhem continued its efforts which culminated in the city’s declaration of “ecosystem neutrality” in 2060. This then brought an end to humankind’s colonialist perspective and invasive influence on nature and natural resources. The declaration of ecosystem neutrality, despite being philosophically flawed and conceptually somewhat vague, was the first large-scale acknowledgement of what we now see as an undisputable fact, and therefore truly deserves the title of "iconic".

Sound recording of Arnhem market place, 2060

How the city of Arnhem looks like in 2100

Arnhem-Noord in the course of 40 years

Curatorial Team

Janthe Buhrs

Eva Couperus

Lukas Schubotz

Sijtie Rensen

The Museum for the Future is a project created by the Urban Futures Studio