With the sinking of the Marshall Islands, it became clear around the world, and particularly for the Dutch people, how important it is to urgently protect the environment. As historians and descendants of the Marshall Islands, we are glad to see that this meant putting pressure on policy makers in the Netherlands and standing up for the Dutch Delta.

With the sinking of the Marshall Islands, it became clear around the world, and particularly for the Dutch people, how important it is to urgently protect the environment. As historians and descendants of the Marshall Islands, we are glad to see that this meant putting pressure on policy makers in the Netherlands and standing up for the Dutch Delta.

With the sinking of the Marshall Islands, it became clear around the world, and particularly for the Dutch people, how important it is to urgently protect the environment. As historians and descendants of the Marshall Islands, we are glad to see that this meant putting pressure on policy makers in the Netherlands and standing up for the Dutch Delta.

As you know now, building floating cities contributed to save at least some parts of the Netherlands. But imagine you are back in 2050 and you are aware that the Netherlands will be flooded entirely in 50 years. You know that somewhere in the world technologies and researchers existed to protect your land from sinking. Now imagine that this knowledge would not have been provided to you.

How would you feel?

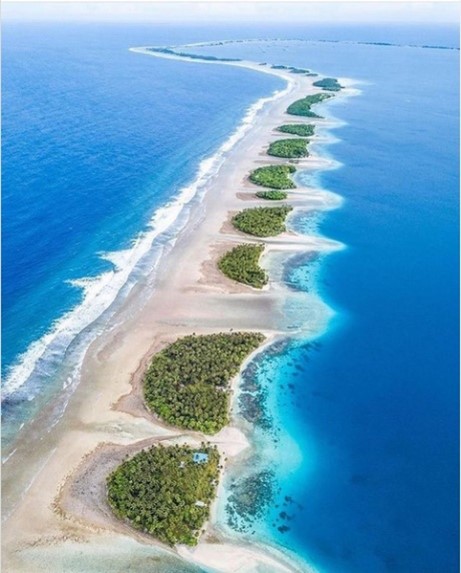

In the early 2000s, this situation was real. Back then, the Netherlands were famous for successfully fighting sea-level rise and positioned themselves as countries’ ‘partner in tackling water, climate and energy issues.’ [1] But some places in the world were not that lucky and would have urgently needed the knowledge and financial support of the Netherlands. Some of those countries are now covered by the sea and with them not only stunning nature sunk but also parts of human history. One of those places was the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) that was comprised of 29 low-lying coral atolls and five reefs stretched across the Pacific Ocean and known for colourful nature.

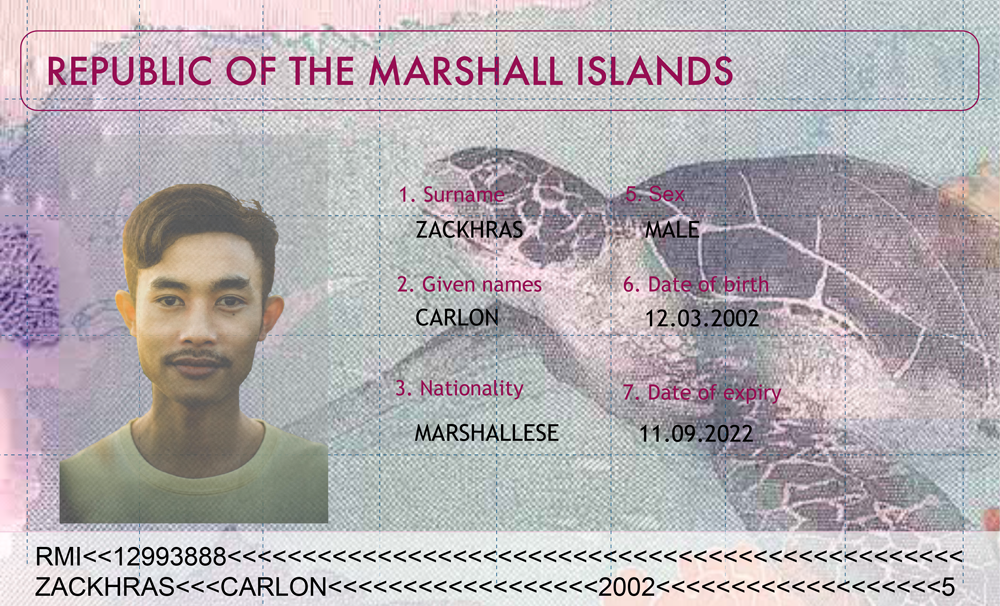

The RMI early acknowledged climate change as one of the greatest threats to local atolls and people. They knew that someday sea-level rise would irreversibly change the islands. But until then, for the Marshallese, it was a stony road. While global efforts continued to explore the nature of climate change, the RMI already faced major impacts on its communities’ livelihoods due to increasing sea-level, sea surge, typhoons and rainfall intensity. Thus, island states had to prepare and adapt to changing circumstances whilst emitting countries, like the Netherlands, were not yet directly impacted. The Marshallese did not accept to be passive victims but became activists for human rights and climate action on the international stage. In the RMI, young people played an especially important role in political activism. One leader of that time was Carlon Zackhras. The climate activist gave his first international speech at the UN climate summit in 2019, at the age of 19. Back then, he inspired young people because he fearlessly stood up for his country.

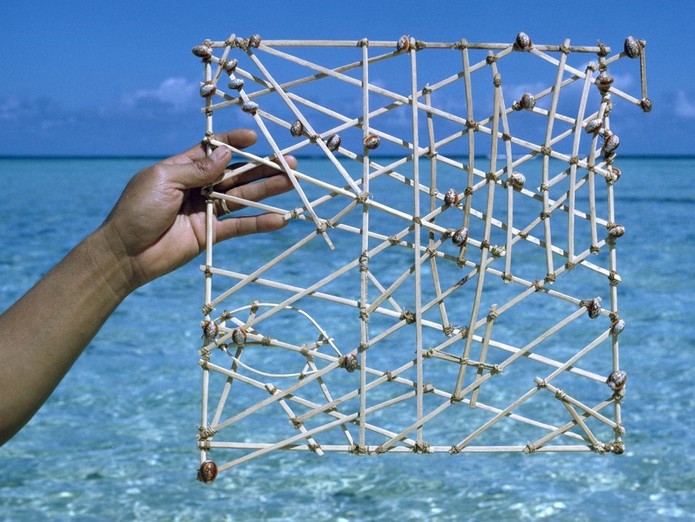

It was clear to the people back then that when the islands flooded, parts of their culture would be wiped away as well. Thus, it was important for the youth to emphasise the incredible history and tradition that would be lost with not taking enough actions. However, on a governmental level, the loss of cultural heritage mostly used to be referred to in connection with buildings or monuments rather than loss of tradition and languages.

In the early 2000s, it was scientifically known that at-risk nations could be protected by controlling flooding through reclaiming and elevating land or relocating inhabitants to urban centres. However, such precautionary measures were often not realised, mostly because of costs. While nations like the RMI could not afford it themselves, industrial nations overlooked their responsibilities

towards threatened places, even though the burdens were often caused by wealthy nations’ lifestyle. So, the RMI relied strongly on external funding often provided by former colonial administrators or aid organisations, like the World Bank, and donor countries, like the United States or Australia. This led to political and economic tensions, accompanied by challenges due to the Marshallese’s colonial history that has made it hard to depend on foreign aid. Furthermore, the financiers used to support only small-scale short-term projects, like improving systems for flood warning or tidal forecasting. Funders held the view that migration would be a suitable alternative for nations to survive. As Ben Graham, a national climate advisor of the RMI, said “there are those who say ... your population is too small to spend half a billion dollars on it. Just relocate. It’s not worth keeping your culture and your sovereign status.” [2] The first islands were flooded in 2035. The remaining islands of this former paradise struggled with an intense scarcity of drinking water and people started to migrate.

Developed nations, including the Netherlands, missed the goals of the Paris climate agreement and failed to fulfil their pledges to support vulnerable states in adapting to climate change, neither with human resources nor financially.

The Marshall Islands – the first nation swallowed by anthropogenic climate change – have sent a clear sign to the international climate dialogue. Worldwide, countries started to realise the importance of taking actions. The Netherlands were pioneers in sea-level rise technology for many years, but after this historic event of the RMI’s sinking, citizens and the government finally realised the importance of protecting the Dutch Delta. Inspired by Carlon’s bottom-up activism for the RMI, young climate activists all over the world started advocating for the climate and their future. Also, in the Netherlands, the youth rose their voices and began to participate in the voluntary missions of the Water Corps Union.

Curatorial Team

Maja Biemann

Freya Endrullis

Rachel Lamothe

Dominique Ernst

The Museum for the Future is a project created by the Urban Futures Studio