From our perspective as Gaia scientists, the salmon populations that went extinct and returned to the river Rhine in the 20th century are a living and breathing symbol of our connection with the earth’s physical systems, of how they have always reflected and inspired the politics of humanity, and of how beautifully (climate)-resilient we can be by working together across borders.

From our perspective as Gaia scientists, the salmon populations that went extinct and returned to the river Rhine in the 20th century are a living and breathing symbol of our connection with the earth’s physical systems, of how they have always reflected and inspired the politics of humanity, and of how beautifully (climate)-resilient we can be by working together across borders.

From our perspective as Gaia scientists, the salmon populations that went extinct and returned to the river Rhine in the 20th century are a living and breathing symbol of our connection with the earth’s physical systems, of how they have always reflected and inspired the politics of humanity, and of how beautifully (climate)-resilient we can be by working together across borders.

— “The salmon has returned, but it is still hiding. We want it to be abundant, as a source of joy!”

Chemicals caused massive casualties among fish and other wildlife downstream

Vibrant waters turning silent

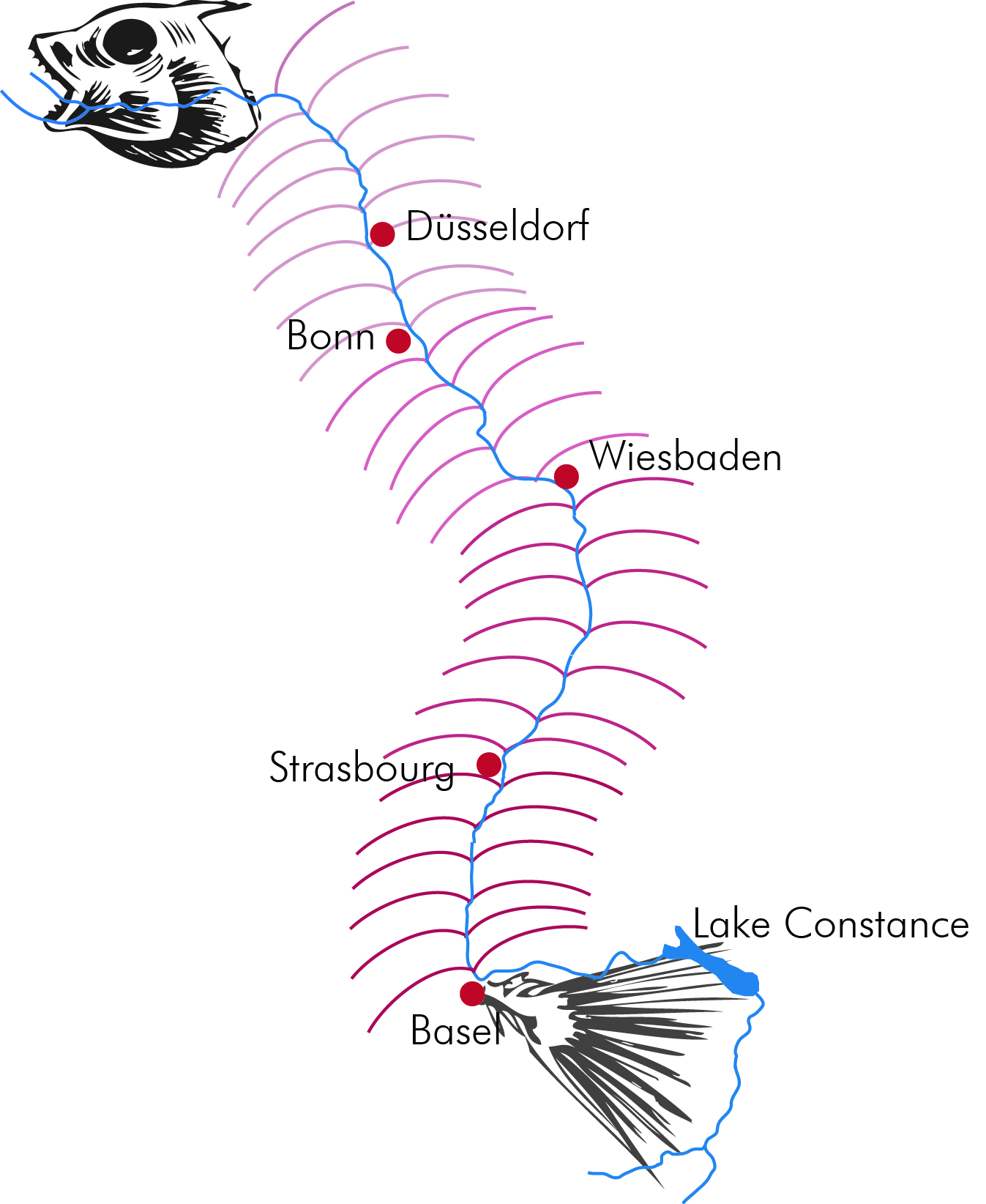

The words of Mrs Perrin-Gaillard echoed at the Rhine Symposium of 1999, where policymakers celebrated their success in raising the river’s water quality (Froehlich-Schmitt, 2004). 100 years earlier, the Rhine had flowed clearly through the heart of Europe and was the largest home for salmon on the entire continent. Each year, millions of Rhine salmon travelled all the way between the Swiss Alps, their birthplace, and the ocean waters of Greenland (Salmon Come Back, n.d.). Yet by 1950, heavy water pollution put severe pressure on the species diversity in the Rhine. The river had been opened to human activities like shipping, irrigation, fishing, and industrial waste disposal. By the 1960s, scientists claimed that the river’s “aquatic ecosystem was virtually dead” (Villamayor-Tomas et al., 2014, p. 363) and the Rhine salmon, once having populated the river abundantly, was extinct. It took a disaster, a desperate cry for help by the river, to remind people and policymakers that the Rhine should be protected as one whole - and to bring it back to life.

Back then, commercial interests were seen as incompatible with ecological concerns, and upstream countries did not consider the problems their waste streams created downstream. What has long been taken for granted today – international cooperation in the context of the environmental crisis – was thus still a novelty. Furthermore, Europe was politically divided in the aftermath of two world wars. Yet, the pollution of the Rhine was not a problem that allowed itself to be addressed individually. As we know, the river has always flowed unbothered by political borders. By its nature, in 1950 it gave birth to a first international effort: the ICPR, short for International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine, was founded to monitor and regulate its waters, on which many beings relied for life and trade (ICPR, n.d.-b). But while the Commission listened to the salmon’s cries for help, because it was bound by the priorities of national ministers, it had little authority to reply with binding measures.

Logo of the International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine

Blood Red Waters

The Sandoz chemical accident of 1986 is considered a turning point in this regard (Froehlich-Schmitt, 2004). The explosion and subsequent spill proved poisonous, almost wiping out the entire eel population, and affecting human populations near the Rhine up to 400km away (Umweltbundesamt, 2011). Finally, the Rhine’s international economic and ecological significance was made clear. The New York Times (New York Times, 1986) wrote that the huge chemical discharge created “havoc in four countries''. People gathered in many river cities to demonstrate, form human chains, and call for an international tribunal (see photos). The disaster was so dramatic that it was compared to the Chernobyl disaster of that same year, with comparable international ramifications. In France, cries of "We don't want to be tomorrow's fish" rang through the streets.

The tragic event also showed that both assessing the extent of a disaster and convicting those responsible was difficult. Not only the environment, but international cooperation was at risk: the French Environmental Minister, Alain Carignon, accused Switzerland and Sandoz of failing to warn other countries in good time. Moreover, even though the spill happened “directly at the West German-Swiss border, there was no exchange of communication between the two countries” (Umweltbundesamt, 2011).

This disaster represents one of the first points in history where it was explicitly recognised that the Rhine is one complex ecosystem connecting people across countries, and that its management could no longer be dealt with along national borders. The notion of transnational water collaboration was captured legally some years later in European Union law (ICPR, n.d.-a), allowing the ICRP to pioneer a series of concepts and strategies such as ecosystem governance, some of which are still championed by institutions like the Rhine Parliament today.

The 1986 chemical spill was followed up by protests in 4 countries

Data shows the fatal effects of Sandoz reached over 400km downstream

The Salmon’s Legacy

Observing them along the banks of the river, the salmon tell an impressive tale of the river’s unity, a system that cannot be divided along national borders. As the Swiss newspaper Tagesanzeiger (2012) reported, In the year 2012, for the first time since their disappearance, salmon swam all the way up the Rhine until they eventually arrived in Switzerland - this was made possible by transnational efforts. The salmon’s disappearance reminded humanity of the water’s connecting power and sparked one of the first transnational efforts to manage the river as a whole.

Curatorial Team

Stefan Gevaert

Silja Kessler

Mira Piel

The Museum for the Future is a project created by the Urban Futures Studio