Every two years, 41 citizens from the catchment area of the river Rhine are selected at random to become members of the Rhine Parliament. There, they listen to and protect the interests of all beings in the river’s ecosystem by means of executive power. For Gaia scientists like us, the Parliament stands for a new wave of politics that recognises the symbiosis between culture and nature, and gives both the power to speak.

The Rhine Parliament is an established institution that most people are familiar with. But do you know exactly how it works? And how does the river participate in decision-making?

Every two years, 41 citizens from the catchment area of the river Rhine are selected at random to become members of the Rhine Parliament. There, they listen to and protect the interests of all beings in the river’s ecosystem by means of executive power. For Gaia scientists like us, the Parliament stands for a new wave of politics that recognises the symbiosis between culture and nature, and gives both the power to speak.

The Rhine Parliament is an established institution that most people are familiar with. But do you know exactly how it works? And how does the river participate in decision-making?

Every two years, 41 citizens from the catchment area of the river Rhine are selected at random to become members of the Rhine Parliament. There, they listen to and protect the interests of all beings in the river’s ecosystem by means of executive power. For Gaia scientists like us, the Parliament stands for a new wave of politics that recognises the symbiosis between culture and nature, and gives both the power to speak.

The Rhine Parliament is an established institution that most people are familiar with. But do you know exactly how it works? And how does the river participate in decision-making?

Science as Ritual

The Rhine Parliament works as a citizens’ assembly, and stands as one of the most prominent examples of this form of political organisation. Assemblies are more common now because the old practice of electing officials often led to the domination of some groups over others, and of the short term over the long term. Instead, members of the Rhine Parliament are randomly selected, while considering demographic as well as geographical representation of the Rhine catchment area. The Parliament seeks consensus in its decisions, with the best interests of humanity and nature intertwined. In this way, it follows the example of the Māori and Hindu cultures that inspired its advocacy for the river in the first place. Of course, some still believe that claiming to speak for water advances the idea that humanity is superior to nature, a perception that our society was thankfully able to move past in the last decades. This is why the Rhine Parliament maintains a number of ritual listening practices:

On the mornings before the Parliament meets for planning and development decisions, each member collects water samples from the river bed that is nearest to them. These samples are assessed in a livestreamed ceremony. If any of the samples are contaminated, or if a member has observed a clear sign of ecosystem disruption, the Rhine Parliament suspends any approval for new economic activity that makes use of the river ecosystem, until the source problem is addressed. This was the case in 2067 when post-Mia apartment reconstruction was put on hold for months to investigate rising phosphorus levels just downstream. The process represents the roots of the Rhine environmental movement, and gives a voice to the river. Like this, the Parliament equips the river with a veto power – a way of negotiating that gives the Rhine room to respond.

New assembly members are advised by local elders and scientists on everything that is important for a harmonious functioning of the Rhine ecosystem. While you will find traditional lobby groups like the “Water Corps Union” or “Future Farmers Force” emphasise the role of humans in nature-friendly solutions, the key innovation of the Rhine Parliament is found in the way it listens to non-human voices. Echoing the work of Joe Gray (2020), each of the various entities of the river are assigned proxy persons: for example the “proxy for the Rhine salmon” and “proxy for the Rhine seagrass”. These proxies provide the members of the Parliament with “their best-informed understanding of the interests of the non-humans to whom they are assigned”, to speak in Gray’s words.

Hurting Our Rhine

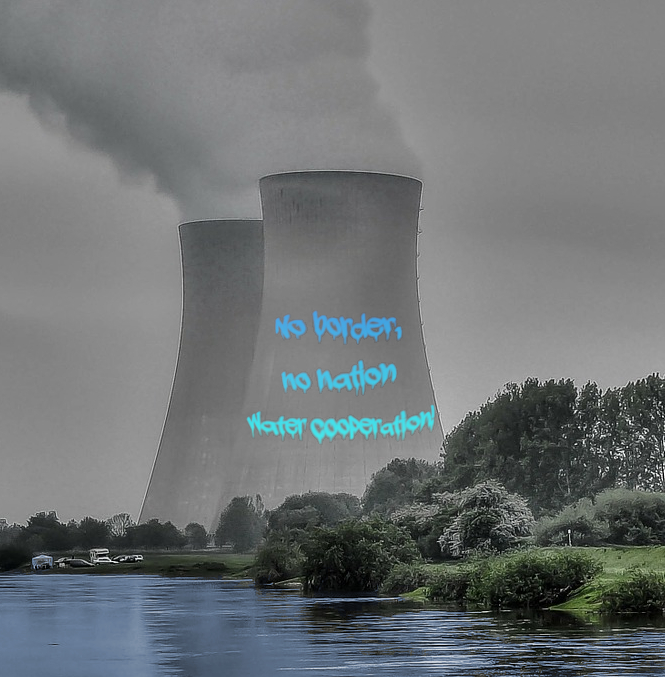

It is crucial to recognise that the common idea of nature as a partner that can contribute to political decisions was long opposed, and found its way into the European spotlight only thanks to the massive civil protests of the ‘30s. A power vacuum had stealthily accumulated around water governance as water directives collapsed with the EU and were replaced by vague promises of future agreements between councils. In particular downstream nations suffered under the unregulated pollution of their aquaponics and drinking water, leading to mass strikes from farmers who were promised control over “their own resources” during the war. The NGOs “Unser Rhein” & “WaterMensen” were born from residents of the river basin who had enough of the disrespect shown to their river. On June 26th 2039, the old protestsong “In The River” reached nr 2 in the German charts. Two days later, Hendrik Bachmann, the mayor of Cologne, captured this sentiment in a scathing speech on national television with the famous words:

“We are the river, and by hurting the Rhine, you are hurting us!”

During the summer of 2039, citizens in dozens of Rhine cities came to the streets to demand protection of the Rhine for everyone: 'Le Rhin à Tous'

A symbiotic future

The Rhine Parliament was born as an informal legal representative organisation for the Rhine river in 2041. In that year, France had just become the last country in the Rhine basin to grant the river legal personhood. This step recognised that the river and all its physical and metaphysical elements forms an indivisible, living whole which possesses all the rights, powers, duties and liabilities of a legal person. The Rhine Parliament, formed by engaged citizens, then set itself the task of representing the rights of the river before various national courts. It took a long journey, from failing to prevent the iconic Rots in de Branding project to aiding the river basin through a European heatwave and flood Mia. Yet in 2068, the Rhine Parliament finally gained executive power in the Rhine catchment area. It is now able to act proactively to govern challenges and activities that directly affect the river.

In the words of Nobel prize winner Philipp Bernatek in his most recent documentary:

“Water is the element that makes our planet extraordinary - it is the source of all life. It is evident that water connects life, and it connects places. Any activity we impose on the river has repercussions for the whole system. In the past, this has been forgotten, but the flow of water will always force our cooperation along its course. In the Rhine parliament, we learn that there is another way to govern, one that does not separate ourselves from nature but makes nature heard through us. And that gives me hope for a better future.”

Curatorial Team

Stefan Gevaert

Silja Kessler

Mira Piel

The Museum for the Future is a project created by the Urban Futures Studio