Climate change forces us to think differently about building houses. This is most clearly shown by the iconic ‘Emergency Flats’, that represent the forced and drastic change in the landscape of the Netherlands and all the socio-cultural challenges it brought upon. In this exhibition we will take you on a journey along the houses that started out as a temporary fix, but whose rebirth changed society permanently

Climate change forces us to think differently about building houses. This is most clearly shown by the iconic ‘Emergency Flats’, that represent the forced and drastic change in the landscape of the Netherlands and all the socio-cultural challenges it brought upon. In this exhibition we will take you on a journey along the houses that started out as a temporary fix, but whose rebirth changed society permanently

Climate change forces us to think differently about building houses. This is most clearly shown by the iconic ‘Emergency Flats’, that represent the forced and drastic change in the landscape of the Netherlands and all the socio-cultural challenges it brought upon. In this exhibition we will take you on a journey along the houses that started out as a temporary fix, but whose rebirth changed society permanently

Rising Tides

Had you walked into a room in an Emergency Flat in 2066, it would have been like walking into a hotel room, smelling like fresh furniture and fragrant wood. Everything you see is brand new and only placed there because of its basic function. No flowers, no photos, but maybe an open laptop with several tabs open on housing offers in 's Hertogenbosch. Many personal belongings remain packed in slightly busted suitcases, a preparation to move away at any given moment. The whole environment breathes temporality. The tense room feels like a metaphor for losing half of the Netherlands and the former living space it belonged to.

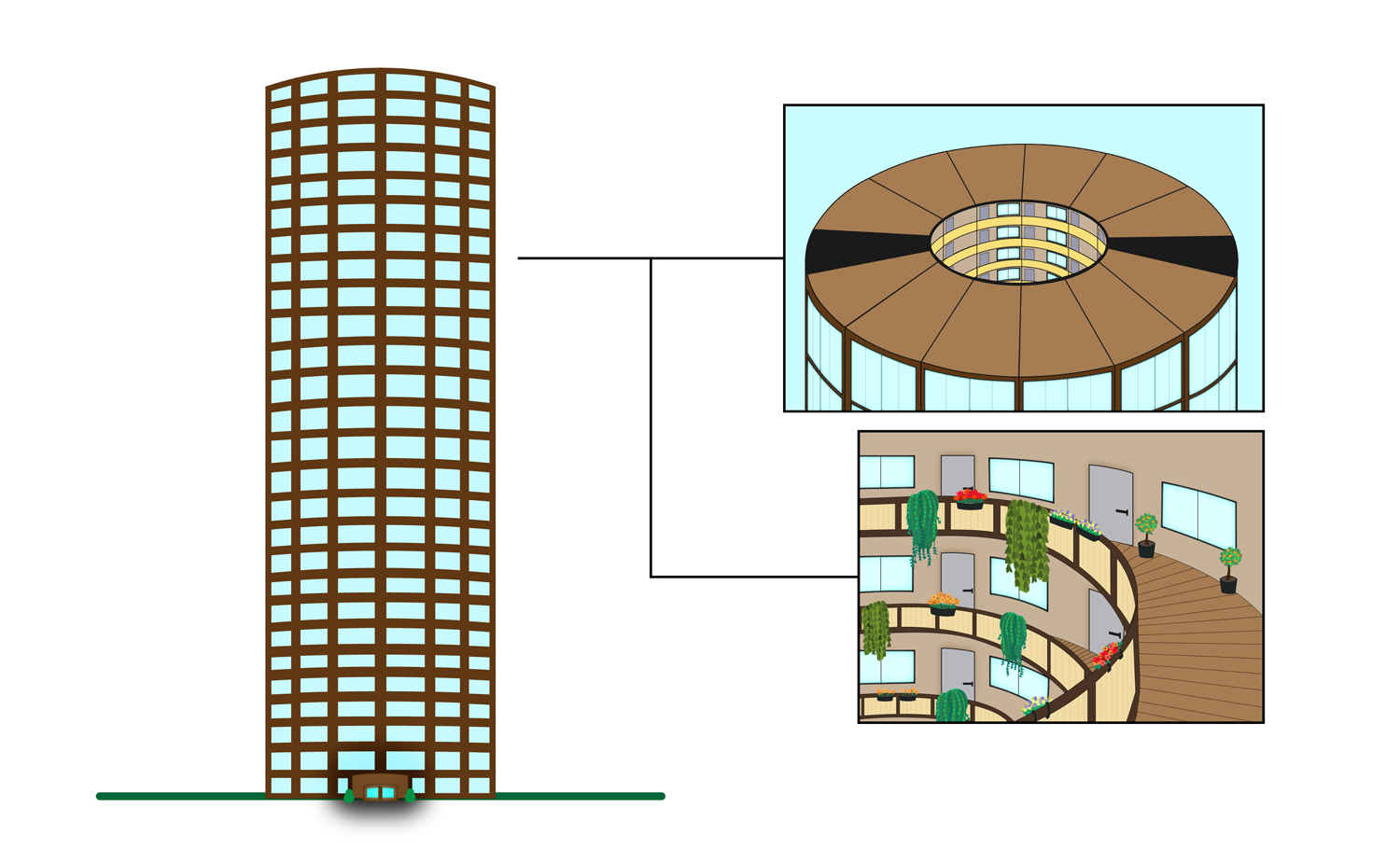

The situation above used to be no exception for the average ‘former’ West-Dutch household. 2066 was a year that left our country in shock: Flood Mia washed away most of the Western part of the Netherlands, leaving only a few higher places. Roughly ten million people had to be relocated to the Eastern part of the country, and fast. Although devasting effects had been predicted long ago, the flood still came unexpected. Former governments were blinded by the promise of a technological fix that would protect the country. The national government in place was facing the biggest challenge since the Third World War. The Ministry of Crisis and Flood Management was installed, and its first plans were executed within a short time frame: emergency housing in the form of 30-story high wooden towers, placed around existing urban structures.

Adapting to climate change: Temporary Building

Before the flood, houses were built with the idea that they could exist for a hundred years. The flood, caused by climate change, disrupted this shared idea. With the premise that the habitable places where we live might become inhabitable, temporary building became the emergency strategy of the Ministry. To build the flats, construction needed to be modular, in order to be flexible and replaceable. Wood was used as building material and every flat was standardised. As the technology at the time did not ensure full modularity of the flats, the Ministry established the Zwolle School of Modularity in Zwolle. The School also sprung off several spin-offs from entrepreneurial students: Bridgular, Modular Movers corporation and WoodRich. These became symbols of the new modular and circular economy.

Within a few months after the flood, 8000 emergency flats dominated the suburban areas around cities like Zwolle and ‘s Hertogenbosch, creating a never-ending skyline. Many people in the North of the Netherlands were opposed to having the flats blocking their view. They stopped protesting after the famous Zwolle agreements by the end of 2066. Support of the population was gained by stating the following famous words in law: it is temporary.

The fast relocation by the Ministry led to the creation of completely new

neighbourhoods, although based on previous municipalities. People from different ethnicities, social classes, backgrounds and religions became

neighbours in the same situation: wanting to leave as soon as possible.

No other options were available due to lack of long-term planning, until a platform emerged on the Evernet where people could swap houses between flats. Still, conflicts among residents were on the rise, people were losing their

patience.

Emergency flat

Changing Tides: how the second life of the flats changed society

To make the best out of the dire housing situation, we students created the start-up ‘Emerging Futures’ to increase the Emergency Flat's sustainability. Living in the flats ourselves, we noticed that somehow, the tide had turned. People handed in a petition for community gardening, and the bulletin boards in central halls slowly became a place to find common interests. Not only within flats, but also between them, because children played together on the common ground around the flats. We decided to build further on this by transforming the central halls into meeting places that facilitated working space on weekdays and hosted informal social activities during weekends. People started to grow plants all over their balustrades and vertical farming was implemented within a short timeframe.

Sustainability efforts in the Emergency Flats by Emerging Futures

Slowly, a transition was taking place. Where municipalities and city governments were still struggling with the energy transition, creating car-free environments and changing agriculture, the development of the sub-urban structure seemed to flourish. Wooden bridges between popular flats were built by Bridgular (inspired by the drawing of a young girl), connecting different flats with different people. In case of another water threat, Modular Movers made sure the flats could be relocated flexibly. WoodRich took care of a fully circular use of wood in buildings. The improvements led to such an increase in popularity of the flats, that there was enough support to terminate the Zwolle agreement in the year of 2071 through a referendum. This made it possible for the flats to stay for undetermined time but they could still be broken down if there was no demand to live there.

Today, 2100, the Emergency Flats are iconic as they show how temporary building, caused by climate change, are the start of a something permanent. Through temporality, they created a new suburban community connected by wooden bridges. It shows, just like the workers' districts in the 19th century, that difficult times are also moments for change. New situations create new possibilities, if we dedicate ourselves to them. The flats have replaced the windmills as the buildings where the Netherlands are the most known for. Just try googling ‘the Netherlands’ and see for yourself!

Image: drawing by Mia (4 years old)

Curatorial Team

Carmen de Vreede

Onno Slikker

Jaimy van Dijk

The Museum for the Future is a project created by the Urban Futures Studio